Taming the Oversized OAuth2 Token: A First-Hand Tale from a BFF Architecture

Introduction

I vividly recall how a seemingly insignificant detail ended up disrupting our entire authentication flow. As an engineer at Omnissa Intelligence (OI), I was on the front line when our frontend-heavy application (with a Backend-for-Frontend (BFF) API Gateway) started mysteriously failing to authenticate certain users. We’d see login attempts succeed, only for users to be immediately logged out or stuck in reload loops. Diving into logs and browser data, we discovered the culprit: an OAuth2 JWT access token so large that it exceeded browser cookie limits, causing the cookie to be silently dropped. This is the story of how we diagnosed the “giant token” problem, learned from industry insights, and engineered a robust solution using envelope encryption to regain control of our sessions.

The Technical Background: When JWTs Outgrow Cookies

JWT (JSON Web Token) is a popular format for OAuth2 access tokens and ID tokens. It’s essentially a JSON payload (claims about the user) signed (and sometimes encrypted) and encoded. JWTs are self-contained and stateless — meaning the server doesn’t need to store session data for them — which makes them convenient for distributed systems. In our case, after a user logged in via OAuth2, our Authorization Server set an HTTP-only cookie on the browser containing the JWT. This allowed the single-page app (SPA) to automatically include the token on subsequent API calls. The catch? Browsers and infrastructure have limits on cookie size. Most browsers cap each cookie around ~4KB, and some proxies or servers enforce a 4KB header limit for all cookies curity.io. Our token, with all its embedded user info and claims and Scopes, was pushing 4KB+ — beyond the standard limit.

What happens when a cookie is too large? Essentially, the browser will truncate it or refuse to store it. In our case, the oversized token cookie never made it intact to the server, so our gateway couldn’t authenticate the user’s session (no valid token was received). The user would appear logged out immediately or get an endless login redirect cycle. It was a perplexing failure: the session failed on the app because the token didn’t stick. Clearly, JWT tokens should not be so large when stored in cookies — as OAuth2 best practices warn, cookies should carry only small, opaque tokens.

Real-World Encounters with Giant Tokens

It turns out we were not alone in facing this issue. In one case, Argo CD (an open source deployment tool) ran into a 4KB cookie limit when their OIDC provider (Dex) was configured to include all of a user’s GitHub groups in the JWT. The JWT ballooned beyond 4KB and hit the browser’s max cookie size github.com. The result? Exactly the kind of login loop and failures we saw. The Argo team discussed alternatives — from compressing the JWT to switching to a session-ID-in-Redis approach github.com. They even noted (as we did) that storing tokens in localStorage wasn’t a safe option due to XSS risks (a common security warning in OAuth circles).

Our own token’s bloat was caused by similarly large payloads — in our case, an abundance of user roles and permissions and scopes etc encoded in the JWT. Another real-world example: users of OpenSearch Dashboards (Kibana) have reported that if an auth cookie grows beyond ~6000 bytes (for instance, by including 50+ group memberships), it simply breaks the authentication flow forum.opensearch.org. Browsers won’t accept such a cookie, and the application must find another way to handle the session. The take-away from industry experience was clear: if your token is too large for a cookie, you need to redesign how you handle sessions. Many modern architectures recommend using opaque tokens (small random strings) in the browser, and keeping the actual JWT data on the server side. We were essentially about to learn why.

First Attempt: Squeezing the Token with Compression

Our immediate reaction to the problem was pragmatic: if the token is too big, can we shrink it? We implemented JWT compression in cookies. The idea was straightforward — compress the JWT payload (using GZIP) before setting it in the cookie, and decompress it in the API gateway on each request. This indeed reduced the size of our cookie significantly. In cases where the original token was, say, 5.0 KB, compression might bring it down under the 4KB limit. For a moment, it seemed we had sidestepped the browser limit.

However, this “quick fix” came with its own costs and headaches:

- Processing Overhead: Compressing and decompressing the token for every single request added CPU overhead. JWTs are used on essentially all API calls in our app, so this was non-trivial load. We noticed increased response times, as the gateway had to unzip the token before validating it.

- Blocking I/O in a Reactive System: Our API Gateway is built on a reactive, non-blocking framework. Unfortunately, many compression libraries perform blocking operations. We found that token decompression was happening on the I/O thread, causing thread blocking in our reactive pipeline. Under load, this threatened to bottleneck the entire gateway.

- Complexity and Maintenance: Introducing custom compression meant more moving parts in our auth flow. It was another thing to maintain, tune, and get right (for example, handling edge cases of compression, potential corruption, etc.). This added complexity didn’t sit well for a security-sensitive component.

In short, while compression technically solved the part of the size issue, it introduced new performance and scalability issues. It felt like a band-aid, not a robust solution. And as our user base grew, even compressed tokens could approach size limits again. We needed a more sustainable strategy — one that aligned with best practices and didn’t fight against the grain of the browser and our framework.

A Better Path Emerges: Going “Opaque” with Server-Side Tokens

Around this time, we revisited OAuth2 fundamentals — the kind you find in resources like “The Nuts and Bolts of OAuth 2.0”. One of the core lessons of OAuth2 (and web security in general) is the trade-off between stateless tokens (JWTs) versus stateful sessions (server-stored tokens). JWTs let you avoid server storage but at the cost of potentially large token sizes and more difficulty in revocation. Server-stored sessions (like the classic “session ID” cookie) keep a small identifier in the client and everything else on the backend, which allows more control at the expense of maintaining state.

Considering our situation, we decided to flip the model: instead of cramming a giant self-contained token into the client, we’d store the token securely on the server and give the client just a small reference to it — effectively an opaque session token. This approach is recommended by many in the OAuth community when dealing with browser limits or security concerns. But we wanted to implement it with a modern, cloud-ready twist: ensuring the token store was distributed and securely encrypted.

Engineering the Solution: Envelope Encryption with Data Keys

After brainstorming, our team at OI devised a solution that borrowed from the concept of envelope encryption (often used in cloud security) — but tailored to our needs. We introduced a two-layer token approach using Data Encryption Keys (DEKs):

- Step 1: Token Issuance (Login Phase) — When a user logs in and our system obtains the JWT from the IdP (or our auth server), the Auth server generates a unique symmetric key on the fly, specific to this token. This key is our DEK for that token. We immediately use this DEK to encrypt the JWT’s bytes (using strong encryption, e.g. AES-256-GCM). Now we have an encrypted token that the API Gateway can later decrypt, but it’s gibberish to anyone without the key.

- Step 2: Secure Storage — The encrypted token is stored in a fast, central store — in our case, REDIS — which acts as a distributed session cache. We don’t want to store the encryption key alongside it (that would defeat the purpose), so what do we use as the lookup key in REDIS? We chose to use a hash of the DEK. In other words, we take the DEK, run it through a one-way hash (for example, SHA-256), and use that hash as the REDIS key under which the encrypted JWT is stored. This hashed key is safe to store (it cannot be reversed to get the DEK), and it’s unique to that session.

- Step 3: Opaque Cookie — Now the Auth server needs to give the client a way to identify the session on subsequent requests. We achieve this by setting a session cookie containing a reference that ties to the stored token. The simplest choice was to use the raw DEK value (in a web-safe encoded form) as the cookie value. This cookie is tiny (just a random-looking string, e.g., 32 bytes base64-encoded) — well under the size limit. Importantly, it’s flagged HttpOnly and Secure, so the browser will send it automatically over HTTPS but JavaScript cannot read it. This small token is effectively an opaque session identifier. (Alternately, one could use a different random session ID and map it to the DEK on the server, but using the DEK directly simplified our design — more on security of this in a moment.)

- Step 4: Token Usage (Request Phase) — When the browser calls our API Gateway with this cookie, the gateway now goes through the following steps behind the scenes: — It takes the incoming cookie value (the DEK) and hashes it (using the same hash method as before) to get the REDIS key. — It looks up the encrypted token in REDIS by that key. Because only our API gateway knows the hash and the original key, this lookup is secure and the data in REDIS is meaningless to any other party. — It retrieves the encrypted JWT from REDIS and then decrypts it in-memory using the DEK provided by the cookie. — Now the gateway has the original JWT in hand (for this request only). It can use this JWT to perform authentication/authorization, just as it did originally — for example, validating it or passing it in an Authorization header to internal microservices. This entire retrieval + decryption process is fast (a small constant-time REDIS lookup and a single AES decryption) and happens for each request. The overhead turned out to be minimal in practice, especially compared to the compression approach we tried earlier. REDIS is in-memory and designed for quick key-value fetches, and hardware-accelerated AES decryption is very efficient.

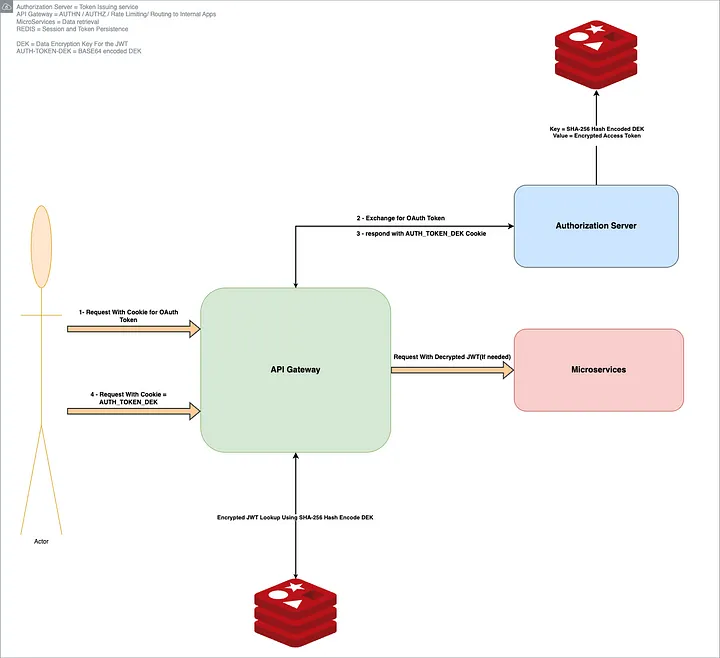

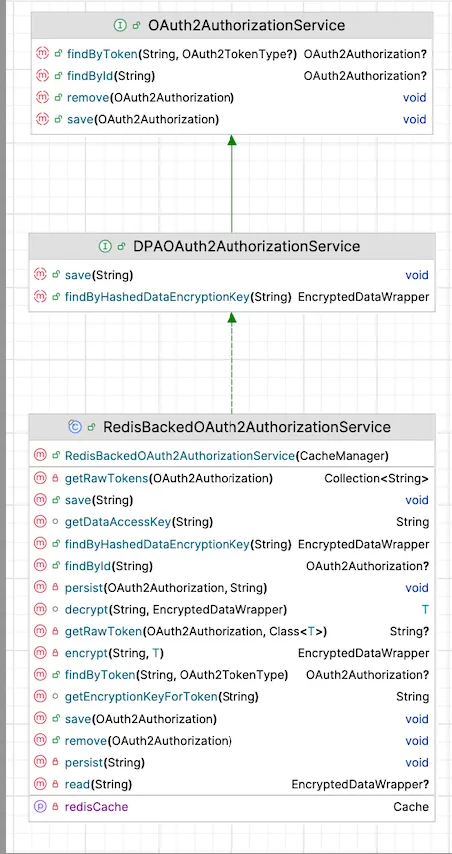

Illustration — Our original approach (red path) stored a large JWT in the browser’s cookie, which exceeded the ~4KB cookie limit and led to authentication failures. The new approach (green path) issues a small opaque session cookie (containing a DEK) to the browser. The actual JWT is stored encrypted in Redis on the server side. The API Gateway uses the DEK from the cookie to look up and decrypt the JWT for each request. This way, the JWT remains encrypted at rest and never travels in full across the wire or into the browser’s JavaScript context.

Security Wins: No Plaintext Tokens Anywhere

This new design brought immediate relief to our size problem — cookies went from 4KB+ to a 32 bytes — but it also improved our security posture significantly. We achieved several security benefits in one stroke:

- No Plaintext Tokens in Browser or Storage: The JWT (which is effectively a bearer token granting access) is never stored as plaintext. In the browser, the cookie holds only an opaque key. In the backend store (REDIS), only an encrypted form of the token resides (and REDIS itself is access-controlled). If an attacker somehow obtained our REDIS data, they’d see only ciphertext and hashed keys — useless without the actual DEKs.

- Isolation via One-Time Keys: Each token gets its own unique DEK. We never reuse these keys. This means even if one DEK were compromised, it decrypts only a single token for a single session, and nothing more. By contrast, if we had used one static key to encrypt all tokens, a compromise would be far more severe. This per-token key isolation follows best practices for encryption. (In fact, Google’s Cloud KMS guidelines note that you should generate data encryption keys locally, use them per data item, and never store them in plaintext cloud.google.com — exactly what we implemented.)

- Avoiding KMS, Achieving Low-Cost Security: Initially, we considered using a cloud key management service (KMS) like AWS KMS to manage our encryption keys. The typical envelope encryption model would have us call KMS to get a new key or to encrypt the DEK with a master key (Key Encryption Key) each time. However, KMS calls would add latency and cost (KMS charges per encryption/decryption request). We realized we could get similar security guarantees without that overhead. By not storing the DEK at all (just its hash), we essentially did what KMS would do (keep the secret out of reach) but within our app. Our master “key” in this design is simply the hashing and encryption algorithm — there’s no long-lived master secret to manage. This significantly cut down cost while still ensuring that no plaintext DEK is ever persisted anywhere. The DEKs live for only the lifetime of the user session.

- Protection Against Certain Attacks: This approach mitigates some risks that come with plain JWT-in-cookie or JWT-in-localStorage schemes: — If an XSS vulnerability existed in our frontend, the attacker still cannot directly steal the JWT token via JavaScript (since it’s not in localStorage and the cookie is HttpOnly). At best, they could steal the opaque cookie — which is still bad (it would allow impersonation as a session ID), but they would not be able to extract the actual token’s contents easily. It also means things like user data in the token (claims) aren’t directly exposed to the browser environment. — If our REDIS were compromised or an exfiltration of session data occurred, the attacker would not get usable tokens. This is a big improvement over a naive server-session store that might keep tokens in plaintext. In our design, an attacker would have to also steal running server memory or break the encryption to get anything sensitive — a much harder proposition. The idea was to make it significantly harder for a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacker or any exfiltrator to access the user’s plaintext token. To obtain it, an attacker would need to exfiltrate and bypass multiple layers of security — potentially including the entire infrastructure — to reach the plaintext keys. Of course, with any design there are trade-offs. In our case, one consideration is that if an attacker manages to steal the user’s session cookie (the DEK) via some means (e.g., by breaching TLS or tricking the user), they could impersonate the user (just as they could with a stolen JWT cookie). Our solution doesn’t magically solve session hijacking — no solution can completely — but it doesn’t make it any worse either. Importantly, it does make certain breaches (like database leaks or log leaks) far safer. We also implemented strict TLS and cookie security flags (Secure, SameSite, HttpOnly) to minimize cookie theft vectors. And revoking a session is as easy as deleting the entry in REDIS — after which the cookie’s key is useless, since the API gateway won’t find any data for it.

Architecture of the final solution — The user authenticates and receives a JWT, but instead of storing it directly, the Auth server generates a random DEK and uses it to encrypt the JWT. The encrypted token is stored in REDIS (distributed cache) with a key that is a hash of the DEK. The browser is given a small, secure cookie containing the raw DEK (session key). On each request, the API Gateway retrieves the encrypted JWT from REDIS via the DEK’s hash and decrypts it on the fly using the DEK from the cookie. This way, the JWT remains encrypted at rest and never travels in full across the wire or into the browser’s JavaScript context.

Scaling Out and Cleaning Up: More Benefits

Beyond solving the immediate token size problem and improving security, our new approach had some happy side-effects on scalability and resource usage:

- Lightweight Cookies and Faster Requests: With tiny cookies, our HTTP requests and responses slimmed down. This reduces bandwidth usage and speeds up request processing (no need to parse huge header, etc.). It’s a subtle performance win, but it adds up.

- Horizontal Scalability via Central Store: By using REDIS for session storage, our solution naturally supports horizontal scaling of the gateway. Any API Gateway instance can decrypt a token because the key is provided in the cookie and the data is in the shared store. We are not pinning sessions to a particular server’s memory. This is a classic advantage of externalizing session state — you can add more servers without worrying about one server holding all sessions. It also provides a single point to purge or expire sessions globally.

- Built-in Token Revocation and Rotation: Because the token is now stored server-side, we gained an easy way to revoke tokens or force logout: simply delete the entry in REDIS(worst case scenario). If a user logs out, we remove their encrypted token from REDIS and the cookie on logout. If a token is compromised or we want to rotate secrets, we can invalidate that session centrally. With pure JWTs stored on the client, revocation is harder (you’d need a blocklist or short expiration). We set our Redis entries to expire at the same time as the token’s natural expiry, so old tokens vanish automatically — no more tokens lingering in browser storage after they’ve expired.

An Unexpected Win: Solving the JVM Memory Leak

Just as we were beginning to see the benefits of this new token encryption model, another unrelated production issue surfaced — one that appeared to have nothing to do with token size, yet turned out to be directly connected.

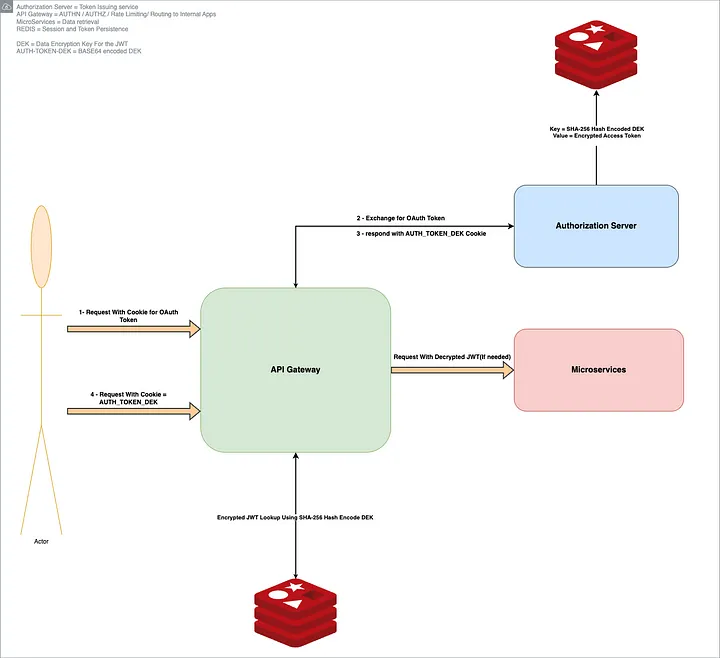

Our authorization service — internally known as the OI Authorization Server — had started experiencing memory pressure. Specifically, we saw an OutOfMemoryError (OOM) in production. This was surprising because the service wasn’t expected to be memory-intensive. After analyzing heap dumps, we discovered that it was holding on to hundreds of thousands of bearer tokens in memory(Expired ones).

Digging deeper, we found the root cause in the default behavior of Spring Security’s InMemoryOAuth2AuthorizationService. This class stores every token generated by the server in a simple Java ConcurrentHashMap, retaining them in plain text, even after expiration. We hadn’t overridden this behavior in our Spring configuration, and over time, especially during a release freeze (when no fresh containers were being cycled), tokens accumulated unchecked.

This was not just a bug — it was a latent architectural vulnerability. Every token generated for the frontend was being stored in memory unnecessarily, causing memory growth that was only mitigated during deployments (when JVMs restarted). Had this gone unnoticed, it could have led to recurring production failures.

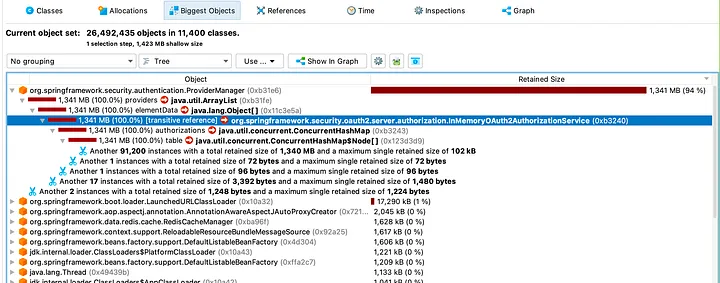

Fortunately, because we had already implemented our Redis-backed, envelope-encrypted token storage system to solve the oversized cookie issue, we were able to reuse the exact same mechanism to fix this memory problem. We introduced a new implementation called

RedisBackedOAuth2AuthorizationService which:

- Avoided in-memory storage entirely

- Persisted encrypted tokens in Redis with short TTLs

- Leveraged the same DEK encryption pattern

With this change, we removed duplicate token storage, improved security posture (no more plaintext tokens in memory), and resolved the OOM condition cleanly. The system now uses Redis as the single source of truth for active tokens, with encrypted data and time-bound retention.

In short, what began as a frontend performance and UX issue ended up surfacing a backend memory leak that we may have otherwise overlooked. Solving the cookie token problem gave us the architecture we needed to resolve this deeper, systemic issue. It was a reminder of how seemingly unrelated problems in distributed systems often have shared roots — and how the right architecture can elegantly solve both.

Reflections and Lessons Learned

In the end, what began as a frantic bug hunt turned into a valuable lesson in architecture and security. We learned that cutting corners with token storage can come back to bite, especially in frontend-heavy architectures. Browsers have their own rules and limits, and we must design within those constraints (or work around them smartly). Our journey led us to essentially modernize the old “server session” concept with a security-focused twist: every session token is encrypted and ephemeral. It’s interesting to note that while JWTs promised to simplify things by being stateless, we ended up re-introducing state — but in a way that scales and remains secure.

For technical leaders and architects, a few takeaways from our experience:

- Don’t ignore token size and client limits. If you’re using JWTs, monitor their size. It’s easy for them to grow over time as you add claims. Remember that cookies max out around 4KB in many cases and hitting that limit will break stuff in confusing ways. If you have an SSO or IdP issuing tokens with lots of data (groups, roles, etc.), be extra cautious. You might opt for reference tokens or reduce the payload.

- Follow security best practices for token storage. OAuth2 literature (and courses like Parecki’s OAuth2.0 Nuts and Bolts) often emphasize not storing tokens in insecure locations (e.g., avoid localStorage for SPAs, due to XSS). Our design to use HttpOnly cookies and opaque keys was aligned with these recommendations and gave us a much stronger security posture than our initial approach. It’s okay to sacrifice a bit of the “pure stateless” ideal if it means your tokens aren’t lying around on clients or logs waiting to be stolen.

- Leverage envelope encryption concepts for custom solutions. We essentially implemented our own mini key management: per-token encryption keys that never get persisted in plaintext. This is a powerful pattern if you need to secure sensitive data at rest without heavy infrastructure. It let us avoid costly AWS KMS calls yet achieve a similar outcome. The principle of never storing plaintext secrets proved to be practical and not just theoretical — even in a high-throughput auth system.

- Beware of default configurations in frameworks. The Spring Security memory store was fine in testing but absolutely not suited for production scale (as evidenced by the OOM and the documentation docs.spring.io). Always double-check how your framework of choice handles sessions/tokens by default. Many will offer in-memory defaults for convenience that you must replace with a distributed store (database, cache, etc.) for real deployments.

In conclusion, our journey to fix an oversized token bug led us to rebuild our authN/Z architecture into a more robust, scalable system. We transformed a frontend session management issue into an opportunity to bolster security across the board. If you’re grappling with tokens in a frontend-heavy app, consider taking a page from our story: go ahead and tame that giant token — your users, browsers, and servers will thank you for it.